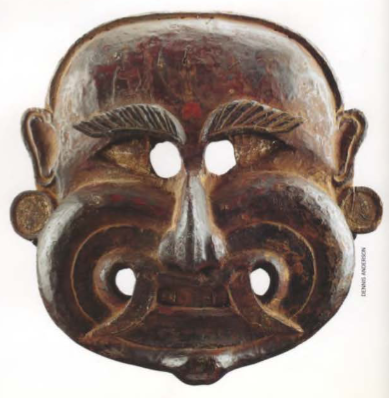

Newari Masks

Summary

This general introduction serves as a primer for further analysis and forms a solid foundation by providing general introduction to masquerade tradition in Nepal and the greater Himalayan region. Masks have a very long history, spanning multiple culture and tradition. Masks seems to have emerged originally in native Shamanism and then gradually assimilated into high culture. In Nepal too, masks play a critical role in spiritual performance and religious mystery. Furthermore, different masks have different purpose: Classical masks represent deities and are used to enact religious mythologies, such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana. Village masks are however used for local dances and generally symbolize local folk-takes. Shaman masks have existed in Nepal from the Tharu community.

Emergence and Overview

Table of Contents

Overview

==Demons and Deities: Mask of the Himalayas 1==

- Imagery of Himalayan mask tradition is derived from [[Shamanism]], village myths, folk-tales and [[Buddhism]].

- The ubiquity of masking tradition suggest a deep and ancient root.

- Masks are divided into three categories based on its purpose and origin.

- Classical Masks

- Village Masks

- Shamanic Masks

- Masks referencing the myths, deities (Hindu and Buddhist), and classical stories like the Mahabharata and the Ramayana are classical masks.

- Classical masks are used for drama and dances.

- Village masks are also used for dances and ritual for their primary content is derived from village myths and folk-stories rather than the religious mythologies or the Puranas. An example of Village mask dance is that of [[Indra Jatra]]. Indra Jatra is a local festival with local myths so masks used in enactment of such myths are village masks.

important

One thing to be noticed about masks and figures is that they’ve been developing across civilization and culture quite parallel and independently. Furthermore, more of the characteristics of such masks are common across those myriad cultures. Take for example the characteristic huge circular eyes present in both Newari Lakhe masks and a Gorgon figure.

Fig: Gorgon Figure from an early Corinthian Vase | 5th BC

Fig: Lakhe mask | 1900 AD

These two masks portray the striking similarity between two wildly different cultures. Not only is the prominent circular eyes feature of both the masks, even the fangs are somewhat identical.

- Weirdly, similar symbols are found in forehead of both the Lakhe and Indra. Lakhe being the prominent antagonist in mythological stories of Indra in Newari tradition, it may symbolize the underlying harmony between these two adversaries.

Primitive-Shamanic Masks

General Description

- Primitive-Shamanic masks were used for occult practices including cure of disease, etc.

- The culture and tradition of masquerade may have been first developed in Shamanic context, which later assimilated itself into the society, and, consequently, into “higher” society too.

- ==Kalo Batak Masks are extremely rare as it was used by the Batak in funeral rites and typically destroyed thereafter.==

- Shamanic masks from the Tharu tribe are among the most primitive masks.

- Masks from the Tharu community generally fall under the village mask type due to their portrayal of Hindu divinity.

- Masks, though surfacely different, can generally be categorized into groups based on physical attributes (shape, facial adornment) and markings.

- A common pit-fall of deriving conclusions from surface-level analysis of such markings is that often a culture simply borrows a symbol without carrying with it the implied meaning. A mask with a trident symbol engraved on it is not necessarily indication of Shaivism: the tribe may have simply borrowed the symbol of the trident without attributed any implications of Shiva on the mask itself.

- Masks from the Rai and Gurung community indicate towards a sacrificial rite—animal and human alike.

- Old masks were repaired rather than discarded.

Roots and Origination

- Shamanism’s weird journey necessitated development of masks. [[Shamanism| See Shamanism]]

- In rituals, Shamans used to connect with “spirits outside this world.” To fully adopt this role, the used various item, among which masks were one of the most important. Using masks, Shamans were no longer the weird guy sitting next to a tree, but a messenger and healer from another dimensions when donning the mask.

Classical & Village masks

- Advent of the Aryans caused various cultures to mix, including the Vedic tradition, natural spirit worship, and shamanism.

- Buddhism greatly influenced Hindu religious tradition.

- Padmasambhava is a very important character in Buddhist mythology. He is said to have been a Indian Trantric. He is also have said to have convinced various deities to be calm and “defenders of the new faith.”

- Padmasambhava introduced a dance which is still enacted today in form of Cham, where he appears in various animal manifestations.

- Nepalese form of this dance is Mani Rimdu.

- Tibetan masks often portray death—sometimes in a serious note, sometimes in silly.

- This may be due to the very nature of spiritual enlightenment: Ego-death.

- Himalayan masks have similarity with many cultures, including Japan, Alaska, and Khotan.

- Masks keep existing, only changing it’s form with its “psychic deep structure” remaining intact throughout time.

- Though motivation and meaning of many masks have been lost, it can generally be extrapolated from existing data as masks come from the same traditional root and have similar motivations.

Religious Drama

Summary

The dances and drama of the Newars is an enactment of Hindu mythology mixed with local folk-talk. Furthermore, Buddhist and Hindu elements are frequently mixed: Shaivism in particular. These dances and drama are cultic in nature, and may have been a popularisation of initiates-only tantric ritual. Masks and adornments were frequently used. It was essential not only on aesthetic grounds, but for proper ritualistic enanctment of the drama itself. The performs, after wearing such masks, considered themselves to be possessed by the divine. Masks are hereditatry: all masks are associated with certain roles, and that role is passed down the the eldest son, along with the mask, after death of the father. Religion and Art in Newa culture is inseparable from each other.

[[#^1f2770|From Ritual to Theater]]

Overview

- “dyaḥ pyākhã” or “gaṇa pyākh” are god dances or divine dances and drama which enacts a religious mythology where the actors are “possessed.” Most of the masks are used in this dance.

- Masks danced are a common event in traditional Newari settlement of Yem, Yala, and Kwapa including other smaller towns.

- These dances are both Nritya and Natak. They combined elements of both dance and theater by including music and such.

- Furthermore, dances and theater were practically indistinguishable due to the immense similarity between them: both were performed near a temple—oftentimes Tantric.

- Dramas are based of Puranic literature mixed with certain folktales and local myths.

- The common theme of these dramas are fight between Gods (dyah) and Demons (Daitya) to establish (or re-establish) [[Dharma]], with the end always portraying the victory of Gods over Demons.

- Newari Dances are linked to and originated from ancient secret tradition.

==From_ritual_to_theatre (G. Toffin), p.28 2==

I contend that most Newar religious dramas are closely linked to these ancient secret rituals and probably originate from them.

- Dyah Pyakha originate from old pre-modern category of theatrical drama which is reminiscent of medieval English plays, which were played near churches (similar to Dyah Pyakha which near performed near tantric temple.)

- Actors performing such dances and dramas are believed to be have been possessed by the deity they’re playing.

- Such Newari dramas are a vestige of tantric initiate-only culture, which slowly dispersed to a larger audience.

- Despite being a Buddhist majority, such dances generally revolved around the Hindu gods and goddesses. Specifically, a mixture of Shaivism and Buddhism is to be seen.

- Often, clownish characters are included in such dances—potentially for comic relief.

- Roles and masks are hereditary: when a person playing the character of, for example, Bhairava dies, his role and the mask is passed down to his eldest son. Thus, such roles were patriarchal.

- To prepare their body for the incoming divine, actors absent from ~4 days, not eating chicken meat and left-overs. Alcohol is allowed.

- Weirdly enough, it’s not through personal process that the actors become deified, but through external adornment. Masks and bells, when adorned, fully transform a actor to a deity. However, that possession is not ecstatic: the performer is fully aware and conscious, but still believes himself to be possessed.

- Aesthetics are essential: they’re what convert a ritual to a more accessible theatrical performance.

- Furthermore, it seems every Newari (and Nepali for that matter) art takes its root in religion. Indeed, it’s extremely hard to separate religion from Newari art. Be it architecture, or sculpture, or masks; it’s a manifestation of divinity. God is Art, human it’s mortal interpreter.

- Though Nepal Bhasa lacks sufficiently sophisticated vocabulary to express the Aesthetic merit in a transcendental-metaphysical manner, it was nonetheless easy to discern masterpieces from second-rate art.

To Read Further

Gerard Toffin - Newar culture and tradition scholar

From_ritual_to_theatre (G. Toffin), p.27

I have already published a series of research papers on these multifaceted divine dances, grounded on ethnographical materials, especially on the Thecva Navadurgā troupe (1996), the Balami pyākhã dance group from Pharping (2011), as well as the Kārtik pyākhã troupe which officiates in Lalitpur (2012).Gérard Toffin. Ritual as Theatre: The Theatrical Dimension of the Indra Jâtrâ Festival (Nepal). Sucāruvādadeśika: A Festschrift Honoring Professor Theodore Riccardi, Himal Books, Nepal, pp.224-239, 2014, 978-9937-597-13-5. ⟨halshs-01694906⟩